Physical Description

Technical Description

Language: Latin, with occasional French

Date: c. 1500

Vellum. 9.4mm x 15.5mm.

61 ff., missing single leaves after ff. 8(illustration of the Annunciation), 22(Oratio and Ad Sextam, Pslams 22 and 23), 39(illustration of the Crucifixion); f. 32(final page of the seasonal servants) is an added sheet, and the text appears to be continuous from the previous page, although a new sentence begins at the top of f.32.

The only missing leaf that neither begins nor ends a section is f.22, making it more difficult to determine exactly what was present there. The last initial on ff. 22v signals the start of the Capitulum (Ecclesiasticus 24) of the Ad Tertiam of the Hours of the Virgin and ends with the second to last line of this section: "V Domine exaudi or(atione)m meam." The fragment in the first line of ff. 23r is the end of the last line of psalm 123 and the page continues with psalm 124 and so on (moving on with the Ad Sextam). Therefore, the Oratio ("Deus qui salutis aeternae beatae Mariae" to "V Fidelium animae per misericordiam Dei requiescant in pace. R Amen.") of the Ad Tertiam is missing along with the beginning of the Ad Sextam — its opening lines, hymn, psalm 122, and most of psalm 123 (only the last 6 words are present at the top of ff. 23r).

Contents

(1) ff.1r-3v

Calendar, in French

Begins:

Ends:

(2) ff. 4-6

Gospel Sequences

John 1:1-14, ff. 4r l.1 - 4v l.26

Begins: Secundum iohannem. (?)/ In principio erat verbum / et verbum erat apud deu[m] et deus erat verbum hoc / erat in principio apud deum.

Ends: Et / videums gloriam eius glo / iam quasi unigenitia patre / plenum gratua et veritatis. (?) / Deo gratiae.

Luke 1:26-38. (Begins in the middle of 26, ends in the middle of 38.) ff. 4v l.26 - 5r l.30.

Begins: Secundum lucam / In illo tempore. Miss[us] / est gabriel angelus a / deo in civitatem galileae qui nomen nazareth…

Ends: Dixit au-/tem maria. Ecce ancilla Domi[ni] / fiat mihi secundum verbum / tuum. Deo gratiae.

Matthew 2:1-12, ff. 5r l.31 - 6r l.4.

Begins: Secundum mettheum / Cum natus esset Iesu[s] / in bethleem…

Ends: per aliam via[m] / reversi sunt in regionem suam / Deo gratiae.

Mark 16:14-20, ff. 6r l.4 - 6r l.30.

Begins: Secundum marcum / In illo tempore. Recumbe[n]-/tibus undecem disciplu[is] / apparuit iesus…

Ends: illi autem / profecti predicaverunt ubiq[ue] do-/mino cooperante et sermonem / confirmante sequentibus signis / Deo gratiae.

(3) ff. 6v-7.

Obsecro te (masculine use, famulo tuo f.7v.) and O intemerata

Obsecro te, ff. 6r l.30 - 7v l.28.

Begins: (?) / Obsecro te domina sancta / maria mater dei pietate...

Ends: Audi et exaudi me dul-/cissima virgo maria mater dei / et missericordie amen.

O intemerata, ff. 7v l.28 - 8v l.24.

Begins: alia or[ati]o / O Intemerata et in eter-/nam benedicta si[n]gu-/laris et in co[m]parabilis / virgo dei genitrix ma-/ria…

Ends: et post huius vite adgau-/dia ducat electorum suorum be-/niginissimus paraclitus.

(4) ff. 9-32

Hours of the Virgin:

Matins, 8v l.25 - 15v l.2. Begins with antiphon Ave Regina Caelorum.

Lauds, ff. 16v l.3 - 21r. l.13. Ends with a short prayer for the dead.

Prime, ff. 20r l.13 - 21v l.20.

Terce, ff. 22v l.21 - 23v l.11. Missing a leaf between ff. 22 and 23.

Sext, ff. 23v l.12 - 25r l.10.

Vespers, ff. 25r l.11- 27v l.30.

Compline, ff. 28 l.1 - 29v l.2.

Seasonal servants, ff. 29v l.3 - 32r l.19.

Begins: Ave regina celorum. ave / domina angelorum…

Ends: Ora pro nobis deum alleluya.

(5) ff. 33-39v.

Penitential Psalms and Litany

Psalm 6, ff. 33r l.1 - 33v l.24.

Begins: Domine ne in furore tuo / arguas me...

Ends: convertantur et exurbesca[n]t / valde velociter. Gloria patri.

Psalm 31, ff. 33v l.25 - 34r l.30

Begins: Beati quorum remisse su[n]t / iniquitates…

Ends: et gloriamini omnes / vecti corde. Gloria patri.

Psalm 37, ff. 34r l.31 - 35r l.25.

Begins: Domine ne infurore tuo ar-/quas me…

Ends: Domine deus salutis mee / Gloria parti.

Psalm 50, ff. 35r l.26 - 36r l.10.

Begins: Miserere mei deus...

Ends: tunc inponent super altre tuu[m] / vitulos. Gloria patri.

Psalm 101, ff. 36r l.11 - 37r l.47.

Begins: Domine exaudi or[ati]o[n]em mea[m]...

Ends: et semen eorum in se[cu]l[u]m dirigetur. / Gloria parti et filio.

Psalm 129, f. 37r ll. 12-28.

Begins: De profundis…

Ends: ex o[mn]ib[u]s / iniquitatibus eius. / Gloria parti.

Psalm 142, ff. 37r l.29 - 38r l.1.

Begins: Domine exaudi orationem / meam…

Ends: quonia[m] / ego servus tuus sum. / Gloria patri.

Antephon, f. 38r ll.1-7.

Begins: Ne reminiscaris…

Ends: ira-/scaris nobis.

Litany, ff. 38r l.7 - 39v l.35.

Missing a leaf between 39 and 40, which would have contained the end of the litany and beginning of the Short Hours of the Cross.

Begins: Kyrie [e]leison. / Xriste [e]lieson. / Kyrie [e]lieson.

Ends: Avertantur retrorsum et eru-/bescant qui volunt mihi mala.

(6) ff. 40r - 40v

Short Hours of the Cross

Begins:...est hora matutina.

Ends: Sis m[ihi] / solatiu[m] in mortis agone a[men].

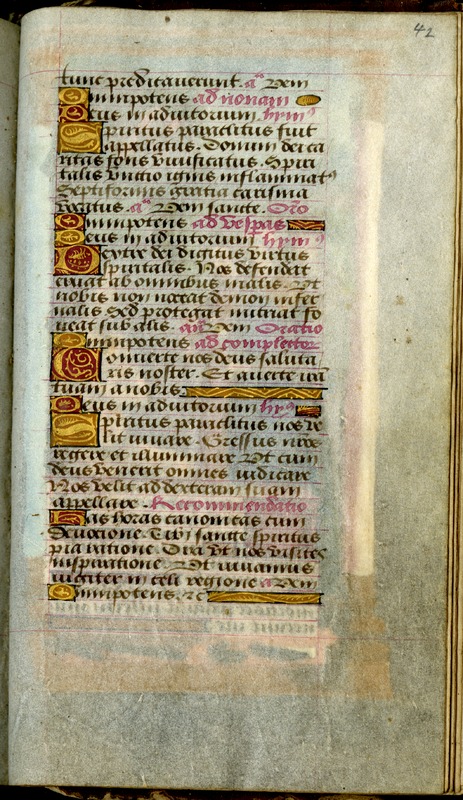

(7) ff. 41-42

Short Hours of the Holy Ghost

Begins: Domine labia mea a-/peries.

Ends: Et vivamus / iugiter in celi regione. De[u]m / Omnipotens. A[men].

(8) ff. 42v.-58v.

Office of the Dead, Use of Rome

Begins:Placebo domino. / Dilexi quoniam exaudi-/et dominus vocem ora-/tionis mee.

Ends: Qui vivis / etcetera.

(9) ff. 59-61

Suffrages

Begins: Te invocamus te adoramus...

Ends: Per X[risti] D[ominum] nostrum.

Script

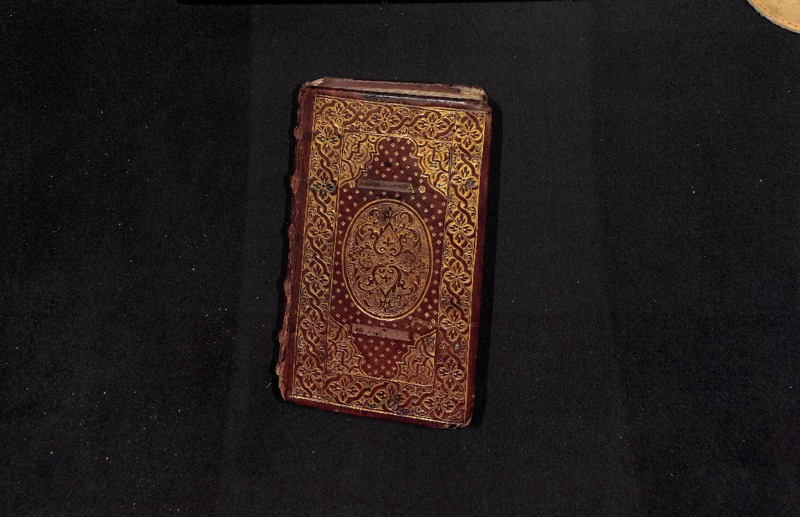

Binding

8.5mm X 14.7mm, smaller interior pattern on covers: 5.5mm X 12mm.

The binding of the manuscrpt, which is not original, is made from French calfskin leather, tooled and gilded. Holes in the cover suggest a set of clasps was once attached to the front in order to keep it closed. The manuscript was rebound by a later owner, possibly for sale: the sides are paneled with broad roll-tooled floral border, central compartments stamped with arabesque corner. A name, possibly that of the original owner, has been carefully scraped away from panels on the sides, partially replaced by the name “Lambert”. Vellum pastedowns and flyleaves, invocation of saints Joseph, Barbara, Benedict, Eustace (Eustachius), Charles, Claudius (***Mary/Carole??***) added on front pastedown. Missing two pairs of ties.

Illustrations (***include slightly longer descriptions of the images.)

21 small miniatures, 6 of which are 13 lines high; 4 full-page miniatures.

Large miniatures: f. 4, St. John of Patmos; f. 33, King David with harp; f. 41, Pentecost; f. 42v, Job comforted by friends.

Small miniatures:

F. 4v, St Luke with lion (should be ox); f. 5, St. Matthew with an angel; f. 6, St Mark with an ox (should be lion); f. 6, Virgin and Child; f. 15v, Visitation; f. 20, Nativity; f. 21v, Annunciation to the Shepherds; f. 23v, Presentation in the Temple; f. 25, Flight into Egypt; f. 28, Coronation of the Virgin; f. 59, Trinity; f. 59, St. Michael; f. 59, St. John the Baptist with the Agnus Dei; f. 59,v, St. John the Evangelist blessing the poisoned chalice; f. 59v, SS. Peter and Paul; f. 59v, St. James the Greater; f. 60, St Christopher; f. 60, St Sebastian; f. 60v, St. Mary Magdalene; f. 61, St. Catherine; f. 61, St. Barbara.

Script, Punctuation and Abbreviation

(Hold for description of script/handwriting/# of scribes)

The punctus is used frequently to mark the end of a sentence, rather than to indicate a pause. The punctus versus, which marks a strong sentence end, is not used, supporting a late medieval creation date: the versus had mostly fallen out of use by the end of the eleventh century. The colon, which took the place of the punctus elevatus in the fourteenth century, is used to mark full and medial pauses.

The ash (Æ) is used in the litany and several times elsewhere, but is not overwhelmingly common.

Et is generally used to represent “and”, and ampersands are not present.

Abbreviation is common and fairly regular, though many phrases are abbreviated only in locations where doing so would save necessary space. Phrases or antiphons which are repeated multiple times within a section are generally abbreviated. Often, particularly in the Litany and Hours of the Virgin, the antiphon orum is abbreviated, as on f.38v. Omnes is frequently represented by “oms”, and daudi by two connected “d”s. Amen is often written as an A or Á.

However, some important phrases are consistently written out, two notable examples being ora pro nobis (“pray for us”) and iesu cristi. (Cristi alone is often represented by the chi, "X", as seen in the Suffrages.) Sancte is abbreviated in the Suffrages, but not in the Litany. The antiphon oratio is not abbreviated.

There are 36 lines of text per page, headings in purple-red or occasionally brown. Ruling in light brown ink visible on top, bottom and sides of most pages. Text written in dark brown ink, capitals touched in gold, line fillers throughout in designs of liquid gold on brown and red panels. On pages taken up by full-page miniatures, no independent text appears.

The use of red ink in headings is most likely a matter of convenience, as the bright color stands out against the dark brown or black text (serving to highlight certain verses for speech when praying with others or for special individual consideration) and vermillion ink was readily available at the time of this manuscript’s creation. While there is no way to tell visually what chemicals were used in the ink, examining contemporaneous manuscripts which have undergone XRF spectroscopy (such as the Portland State French Book of Hours) suggests that it likely contains cinnabar, an inexpensive and highly sought-after pigment used in vermillion ink.

There is one column per page, excepting the Calendar, which contains two columns on each page. Subdivisions occur in the text when illuminated versals appear. Versals take up four lines each and are red or orange ink with initials in gold leaf. Once again, the Calendar is the exception to this, with red and gold versals at the head of each column which take up two lines each.

The mise-en-page of this manuscript is similar to that of a manuscript produced by Guillaume Le Roy, a descendant of one of the first printers working in Lyons. The Le Roy workshop produced both printed books and manuscripts, suggesting that it is indeed possible the Lewis & Clark manuscript was made in dialogue with print Books of Hours.

Provenance and History

The Lewis & Clark manuscript was created circa 1500, a date which is supported by the anachronistic dress of the figures it contains and the structure of its prayers. As well, its regional Litany of the Saints was a slowly disappearing feature by the time of the manuscript's completion. The emergence of printing and the mass production of books of hours in the early 16th century brought with it the standardization of many features, like the illuminations and the Litany of the Saints. Instead, Books of hours began to base their Litany of the Saints off of the Roman model, one with fewer saints that ignored the regional cults that populated previous litanies. This development affects the dating of the Lewis & Clark Book of Hours’ in two ways. First, it limits the timeframe of its creation, as a specially-commissioned manuscript book of hours would have become less cost-effective as printing improved during the first few decades of the 1500’s. While illuminated manuscripts would still be made, printed books would overtake them in the market (and eventually oversaturate the market, given the dramatic fall in books of hours sold in the middle of the 16th century). Second, the rise of printed books of hours and the standardization of their contents gives this manuscript a certain “last of its kind” quality. While printed books of hours could display great deals of creativity in their illustrations and in their contents, the unique litanies that resulted from patrons including their local saints were lost.

Furthermore, the Litany of the Saints in the Lewis & Clark Book of Hours gives the impression that it was commissioned and possibly made in Western France. The presence of four saints from Western France (Leobinus, Eutropius, Martial, and Dionysus) indicates that the manuscript was made for a reader who had an extensive familiarity with these saints through mass or through interacting with their relic shrines, as both Martial and Eutropius had reliquaries dedicated to them. This leaves two possible explanations for the manuscript's origin, both of which may be true: that artisans from Western France produced it or an individual from Western France commissioned a Book of Hours that featured saints he recognized from his surroundings.

Having established the area of origin as Western France, a Book of Hours from Bourges of the same dating and style of the Lewis & Clark manuscript is an ideal candidate to juxtapose with it. The majority of feasts, especially red-letter days, of the Bourges calendar are identical, though perhaps more neatly written out in full (with no abbreviated names or titles). This is a testimony that supports the theory that the the Lewis and Clark Horae also hailed from Bourges. However, there are three pieces of evidence that do not corroborate the same theory. In the entry for January 30, the Bourges calendar celebrates a Saint Blanchard, while the Lewis & Clark manuscript lists one “Babille.” This name is not a recognized Saint by any official standards. However, a small handful of accounts of French folklore reference a holy Babille (meaning talkative). The only record of a physical veneration, a carving in wood, appears in Pont-de-Cé, in the Church of Saint-Maurille of Angers, France. Babille is a woman of folklore who was bound with locks and her mouth shut with a padlock. It is unclear why or how she was venerated, but a rough translation of a French Glossaire Etymologique from 1908 records the carving in Angers and reveals she was a folklore “symbol of silence that she never observed,” and “a threat to what may come to those who do not remain or respect silence”. This piece alone, though interesting, would be far fetched to make a decisive argument for our manuscript’s place of origin. However, the city of Angers surfaces again on September 12 of the calendar, where Saint Maurille– the patron saint and Bishop of Angers– is celebrated with a feast day. (The saint's official feast day is the 13th, suggesting that this is an error in later annotations of the manuscript).

Another item of evidence for the region of Angers, France, is a pair of entries-- November 10 and 11, the latter as a red-letter day. The calendar has designated both of these days to saint Martin who became Bishop of the city of Tours in 372. In the Bourges manuscript, the November 11 and his official feast day is celebrated, but the extra day in our calendar could be an inscription error, or could signal proximity to Tours as a cause for emphasis on Martin, seeing as the city of Tours is a mere 60 miles from Angers. In the Litany there is yet another indication for Angers, where regional saint Maurus is present. Like Maurilius, Maurus was an established figure in the history of Angers, and he established a Benedictine monastery along the banks of the river Loire, just a few miles from Angers, called Glanfeuil Abbey. Like Babille, he is likely a fictional figure, and is worshipped exclusively in “local calendars”.

All of this allows the region of origin to be confirmed as Western France and include (and even prioritize) the city of Angers, France.

The book contains the eighteenth-century bookplate of P. Goyet, who owned a sizeable collection of manuscripts including the Bryn Mawr College MS Gordan 28 and a printed Montaigne of 1659 (now property of Harvard’s Houghton Library). Goyet was a resident of Villefranche, most likely Villefranche-de-Rouergue, which is located in South Central France.

The book may have also spent time in eastern France. The pastedown on its front cover was written at least a century after the book was made, seem to indicate that the book was once in eastern France, in the modern region of Franche-Comté. The script shows some Humanistic influence, which may be a result of the book's proximity to northern Italy.

The pastedown contains the names of several saints, some of whom are generally included in books of hours, and some of whom are regionally specific to eastern France. For example, St. Eustachius refers to St. Eustace of Luxeuil, a Burgundian monk from the mid-6" century. He was a monk at the abbey in Luxeuil, which became Benedictine after his departure. St. Claudius of Condat, or St. Claude, was a 7th century monk and bishop who began his priestly life at Condat Abbey and later became the bishop of Besançon—an interesting connection, considering that city’s significance in the production of Books of Hours. St. Carole refers to St. Charles Borromeo (1538–1584), the latest of the saints listed. He was the Archbishop of Milan, and an advocate for religious education for children through the catechism. The location of Condat (now Saint-Claude), Besançon, and Luxeuil in the same region of eastern France, and the proximity of those cities to St. Charles’ home of Milan, supports the conclusion that the book was in eastern France during the 17th century.

The manuscript was purchased by Lewis & Clark at the New York Antiquarian book fair in 2014 from (dealer’s name**).