Artistic Style and Context

Border illustrations are present in the Gospel sequences (f. 4v, 5r, 6r), the Hours of the Virgin (f. 15v, 20r, 21v, 23v, 25r, 28r) and the Short Hours of the Dead (f. 60r, 60v, 61r). These resemble those present in print Books of Hours, particularly in their rigid, somewhat geometric structure. However, each page of illustration is unique, marking the manuscript as more similar to early handmade Horae. Chrysography is evident throughout, though usually in the form of a gold wash rather than gold leaf.

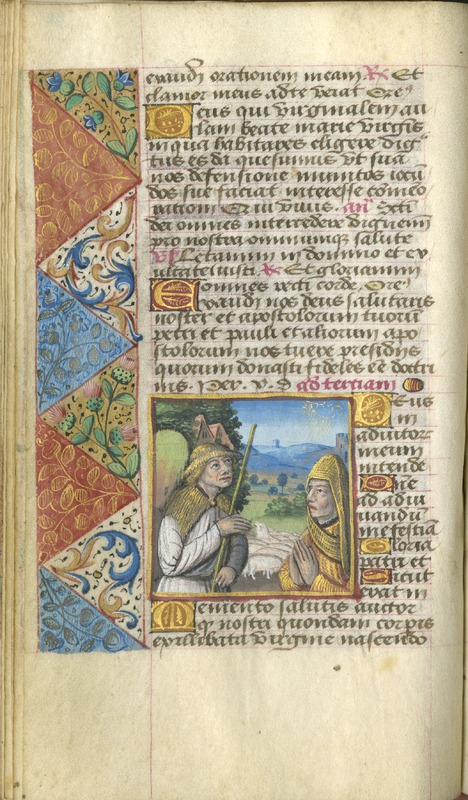

Figures are depicted anachronistically, in clothing that matches neither their respective time periods nor the creation date of the manuscript. Biblical figures like Mary the Mother of God, King David, and the Prophet Job are depicted in clothing that is reminiscent of the Early Middle Ages, fifth through eleventh centuries, rather than the clothing of their respective times, Roman Judea and Ancient Israel. The fashion of the Early Middle Ages had men and women dress almost identically. In sixteenth-century fashion, women retain the long dress with new shapes and designs while men wear increasingly shorter clothing and tight hose. The design and color of the older fashion is much more simplistic and often outfits would have just one or two colors in their ensemble. The newer fashion featured many colors and intricate designs that showed off the wealth of the owner, but this is not seen in the Lewis & Clark manuscript. However, images of royalty (such as King David, f. 41) show figures wearing ermine, a symbol of wealth which became especially popular in the early sixteenth century, supporting the presumed sixteenth-century date of creation.

Marginalia are extremely limited; most marginal focus is on border illustrations. This may be because the owner was unable to pay for additional work to be done on the book (and that it is, in that sense, “incomplete”), or because the full-page illustrations and borders were lavish enough that marginalia was forgone.

The main marginal decorations in the Lewis & Clark manuscript are highly realistic images of flowers. These resemble the work of Le Roy, as above, in the sense that flowers are not grouped by season or region. While they are not exact enough to be identified with certainty, recurring flowers may be carduncellus caeruleus (the blue safflower) or omphalodes nitida (navelwort).

Often, when borders are present in the manuscript, they consist of either the floral motifs mentioned above or more geometrical images such as triangles or stripes of color. At other times, particularly in the full-page illustrations(as seen in the figure of King David, right), the borders are more intricate, depicting marble pillars and taking up the entirety of the page. This intricacy in the full-page illustrations may be a major reason why several leaves which likely contained them, such as the opening to the Hours of the Virgin (after f.8), are missing. They could have been sold as works of art separately from the rest of the book, a relatively common practice.

In fact, the image of King David (above) which opens the Penitential Psalms is an excellent example of the intentional construction of the manuscript's full-page miniatures. A block of text, the beginning of Psalm 6 and thus the beginning of the section of the seven Penitential Psalms, rests below David and between the architectural pillars that frame the miniature as a whole. These pillars, one blue and the other red, draw the eye inward to the start of the Psalms and also to the image of David that accompanies them. The attention of the reader is also drawn to the text with the help of the four-line red, blue, and gold littera notabilior (in this case, the "D" in "Domine"), red and gold line fillers, and red rubricating of the opening of the Psalms — "Ant: Ne reminiscaris. Psalmus." King David catches the attention of the viewers as well: he is also decorated in gold, and this detailing is used to create the appearance of folds within his robes as well as provide a brighter contrast against the brown background and darker blues and greens of the other figures' robes.

This level of detail, especially in terms of color, was not possible to achieve in the print books of hours of the time. The absence of color requires shading to account for illustrating depth instead of pigments and brush strokes. The lack of color also robs the printed book of the ability to guide the eye of the reader to significant figures, as is achieved in this book of hours by washing King David in gold, coloring initials, and rubricating the opening lines of the psalm. The man watching David from behind the curtain is the only other figure washed in gold, suggesting that he is of equal importance to the king and could therefore be a divine figure. Overall, the composition of the King David miniature emphasizes the importance of image in relation to text while illustrating a long tradition of the association of King David with the Penitential Psalms, and thus introducing the section in the most conscious way possible.

The unique composition of the figures makes it difficult to identify an artist or a definite city of origin, but it also assists in ruling out certain areas which had radically different styles or methods of production. Lewis and Clark’s book of hours is odd in terms of its art style and the composition of its miniatures. The eyes of the figures within the miniatures are abnormally wide and swollen, with high eyebrows and large noses. Their heads are proportionally small to the rest of their bodies, and there are visible brushstrokes, particularly in the hands. Such abnormalities make dating or otherwise attributing this particular book of hours to any one artist or workshop immensely difficult, as they are so outside the relative norm of manuscript art.