Manuscript Production and the Influence of Printing

The book trade in late-medieval Europe brought with it the beginnings of a confluence between old and new forms of manufacturing. On one hand, until the advent of European printing in the 1450s, every book was a unique, handcrafted item, laboriously constructed from expensive materials by skilled artisans. Even when printing and quality paper lowered the cost of book production, it remained largely the domain of individual patrons and artisans. However, the organization of book production and trade, the methods used in their manufacture, and their proliferation among the upper classes hinted at later developments to come in the pre-industrial economy.

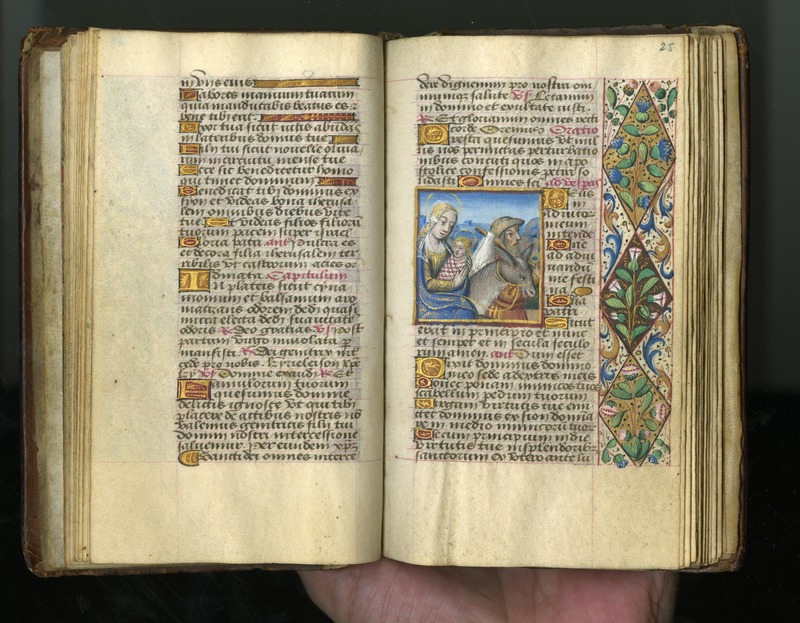

As many have noted, no text represents the book trade in this period better than books of hours. Each of these books possesses a history as rich as any piece of art or jewelry, and is made all the more personal by its role as companion to the private prayers of its past owners. Each is, as Virginia Reinburg puts it, “both artifact and goods,” informing cultural, religious, political, and economic history, in addition to the purely aesthetic beauty of the medieval codex.

The 16th century French book of hours in the possession of Lewis & Clark College is a fine example of a later handwritten and hand-illustrated horae which was nonetheless clearly influenced by the advent of printing in which it was made.

Understanding the production and composition of this particular book of hours necessiatates an exploration of the sixteenth-century French book trade in which it was produced and, eventually, sold. Prior to the introduction of print, the book trade in France was centered on workshops in Paris and several provincial centers, particularly those in Burgundy and along the courses of the Loire, Saône, and Rhone rivers. Virginia Reinburg cites Amiens and Troyes, near Paris, Tours on the Loire, Rouen on the Seine, Dijon in Burgundy, and Besançon and Lyons on the Saône as provincial cities specializing in book production, and books of hours in particular. The provincial book trade in late medieval France is representative of the larger urbanization occurring throughout the country at that time, as in the case of Lyons, where strong connections developed between the larger provincial citiy and the nearby towns. Even in the metropolitan capital of Paris, the dynamics of urbanization were still felt, to the extent that one city would exist effectively in the creative and productive shadow of another.

In the geography of the medieval city, the book trade was generally associated with the cathedral. Though their clientele were often associated in one form or another with universities, the book trade tended to gather around religious institutions and in the surrounding neighborhoods. This reflected the kind of industry taking place in the shops of scribes, paper- and parchment-makers, rubricators, illuminators, bookbinders, and booksellers. Though their products were very popular, at least among the classes who could afford them, and had a remarkable geographic reach for the time, artisans in the book trade still operated under a system in which each aspect of a book was handmade, often intricately, by trained specialists who belonged to traditional guilds and adhered to their regulations. Each book was one-of-a-kind, even if it was an inexpensive shop-copy manuscript.

And yet, the in-shop process of making books came to resemble the integrated manufacturing process of early industry: so much so, in fact, that customized books could even be assembled from stock images and texts, as a modern consumer might choose from a predetermined list of options when buying a new car. Indeed, the car analogy is not out of place, as a Book of Hours would often be the singular luxury item a person owned.

All sections of the book trade were dominated by the guilds (known as métier), from the manufacture of parchment to the sale of finished manuscripts to, eventually, printing. The guild for booksellers dated to at least 1275, and initially divided its members into two categories: those who traded in pre-made or used books, including exemplars, and those who made new books themselves. This distinction is of particular interest in relation to Lewis & Clark's Book of Hours, which has been bought and sold several times in its history, and may have covered some geographical distance in its journeys from owner to owner.

The métier also existed to protect the exclusive rights of their members to practice their particular craft, an activity which would quickly become outdated.The idea of the independent libraire efficiently turning out books in his own shop, working in as well as managing it, represents a distinctively medieval mode of production, and the guild system, which privileged the work of a master artisan over large-scale production, existed to support it. The book trade was unique because it moved steadily towards standardization, particularly after printing created more uniform contents for liturgical books. The late medieval book trade possessed characteristics of the guild-based economy of the medieval towns, but was also a precursor to the large-scale production which would ultimately overturn this system. In this way, both the makers and the buyers of medieval French books were on the cusp of the modern economy, but they were still undeniably tied to an earlier mode of production.