Penitential Psalms

Not only did books of hours support an increase in literacy among the general public, they also helped to redefine the medieval reading experience of lectio divina. This practice is composed of three steps in which reading (lectio), meditation (meditatio), and prayer (oratio) culminate in a singular devotional activity. Lectio divina is a tedious process specifically because reading is a sensorimotor activity (silent reading was a product of the Middle Ages and was still developing at this time); thus time and meditation was required in order to reach maximum comprehension when reading privately. This tedium allowed deep emotions to flow between the reader and the text, ultimately aiding the reader in achieving a greater sense of communion with God in praying over a Book of Hours due to the increased ability to contemplate and pray autonomously.

Because of the newfound ability to pray privately using a Book of Hours, penance was no longer reserved for just the church: it now had a more personal and immediate place in daily life. Prior to this shift, the Penitential Psalms were used mostly by members of religious orders that repeated the Psalms in penitential devotion year-round (particularly in England) and especially during the Lenten period and feast days. The seven Psalms were also used in rituals of canonical public penance, such as the tenth-century approach to reading the Penitential Psalms aloud during the severe and dramatic ritual of excommunication on Ash Wednesday (as described in a collection of conciliar canons compiled by Regino, abbot of Prüm, around 906).

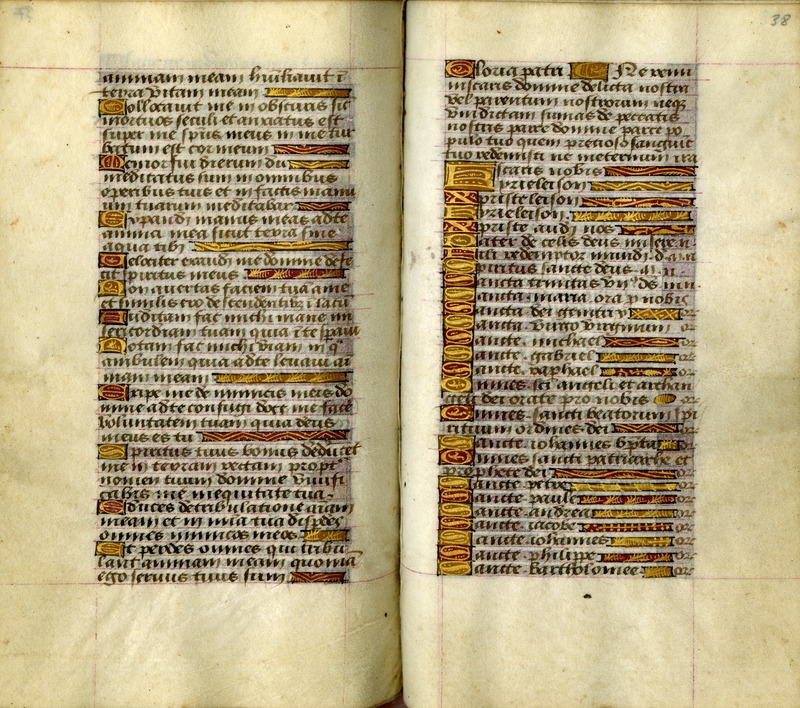

In most Books of Hours, the Penitential Psalms follow the Hours of the Cross and the Hours of the Holy Spirit and precede the Litany of the Saints and the Office of the Dead. One of the functions of the Penitential Psalms — easing the amount of time the dead spend in purgatory — becomes influenced by the Psalms' proximity to the Office of the Dead within the Book of Hours; in this case, the recitation of the Psalms prepares the reader for later prayers to the dead. However, the Penitential Psalms within Lewis & Clark College's book of hours are located between the Hours of the Virgin and the Short Hours of the Cross. While this may dissociate some of the Penitential Psalms from the Office of the Dead, the main goal of the Psalms remains untarnished by order in that the theme of the sinner seeking forgiveness remains constant.

Although they are connected by their association with atonement, the Penitential Psalms themselves (numbering 6, 31, 37, 50, 101, 129, and 142 in the Vulgate) are not consecutive within the Bible. The grouping of these particular seven Psalms may be due to a number of factors, including their shared place within a judicial genre of psalms, their common theme of a sinner seeking forgiveness (regardless of how joyfully or regretfully they do so), or their relation to the psalmist himself:King David. The Psalms are traditionally ascribed to King David seeking penance for his sins, which included adulterous relations with Bathsheba and the consequent murder of her husband, Uriah. Because of this association, the illustrations signifying the start of the Penitential Psalms are usually of King David. One of the most popular depictions of David is of him observing a bathing Bathsheba. This singular image eventually became representative of the collection of the Psalms as a whole, despite their lack of literal relation to the narrative of David and Bathsheba: the only Psalm that would potentially referto this narrative is Psalm 50.

In Renaissance Horae, images focus on King David committing his sin rather than images of David repenting for his sin, David playing an instrument, the Last Judgment, or Christ enthroned — images popular prior to the sixteenth century. Illustrations like this served an important role in reading Books of Hours, in that they were used simultaneously for devotional, catechetical, and pedagogical purposes. Readers of the time would learn to recognize messages within the text by studying an accompanying image. In this case, David brings a message of atonement and is an example for the reader to follow.

In Lewis & Clark College's Book of Hours, a full page miniature of King David (ff. 33r) begins the section of the seven Penitential Psalms. However, David is not depicted with Bathsheba in this image; instead, he is illustrated with a harp, representing his role as a psalmist. David is also in possession of what appears to be a girdle book, which is a Book of Hours wrapped in fabric or animal skin so that it may be secured to a belt and made portable. This suggests his desire to repent for his sins using a Book of Hours, much like the experience of the owner of the book in which this image resides. Behind David on the right side of the illumination stands a woman in blue and a man who places an arm on the woman's shoulder. On the left side of the miniature is a man who peeks out from a curtain behind David; this sneaking figure could represent a heavenly presence witnessing King David's penance, or simply an intruder watching the scene unfold.

If the King David image in Lewis & Clark's Book of Hours does indeed depict David in a penitential state, as suggested by his personal Horae, this image does not reflect the tendency to illustrate King David with Bathsheba. Rather, it goes against the growing fashion of depicting David in the act of sinning and leans towards the older tradition of illustrating David in the act of repenting for an already committed sin. The image within The psalter or booke of psalmes both in Latyn and Englyshe further differs from that within the Lewis & Clark Book of Hours in that the booke of psalmes' image is printed while the Book of Hours' image is hand-painted. This demonstrates the effect of the shift to the printing press on the overall representation of image within psalm books.

However, it is important to consider the possibility that the King David image is not, in fact, a depiction of repentance, and instead shows a different scene in the story of Bathsheba. The image is peculiar in part because David and the other figures in it are all glancing to one side, rather than directly at the viewer, and David is sitting on a platform or stage of some kind. This could be an image of Uriah, Bathsheba's husband, being summoned from battle to appear before David. This is a crucial scene in the story, because it occurs just after King David has impregnated Bathsheba; here, he tries and fails to get Uriah to leave battle and have intercourse with his wife, thus hiding the fact that the child is not his. If this is truly the scene the image is depicting, it does not in fact represent King David repenting for his sins, but instead, similarly to the image of a bathing Bathsheba, shows him squarely in the middle of committing them. This would identify the image more strongly with the traditions of sixteenth-century Horae, both solidifying the early-sixteenth century creation date and suggesting that the artist was in touch with and had experience with other depictions of the Penitential Psalms, even if they chose not to show the story of David and Bathsheba in quite the usual way.